7 Science, labs, crafts, games

Science implies the usage of a new language for all students alike, which makes it easier to include visuals and the senses. Here are some tips to enrich the science classroom in a way that promotes learning for all students, and are especially beneficial for bilingual students. The book by Samway, Pease-Alvarez, & Alvarez (2020) provides detailed ideas of things you can do in the classroom.

- Templates: When speaking about scientific phenomenon, try to use fixed structures and easy language with consistent highlights and repetition of key words. E.g.: El tigre tiene garras para cazar un animal, La jirafa tiene cuello largo para comer de un árbol muy alto

- Images: Use images that illustrate the concept, and strategically point at the visual at the same time you say the corresponding word. Have visuals posted in the classroom where students can point at while speaking or instead of speaking.

- Observation: You may ask students to go outside and observe aspects of nature on the playground. This helps bilinguals learn vocabulary through realia. E.g. You can observe the parts of the plant on a real tree, discuss the water cycle by observing the clouds, experience water under a rainy day, take snow to the classroom to see it melt.

- Experiments: Intervention on nature to analyze its outcomes may feel as play time to students. E.g. Let helium balloons fly away to discuss air, use a stethoscope to hear the heart rates, plant seeds in small pots to observe growth, throw balls of different sizes and weights to test gravity.

- Field trips: While they take time to prepare, field trips to a planetarium, museum, botanical garden, or aquarium help bilinguals get a sense of the space they live in. Their parents may not know those places or may not have the money or time to take children to family field trips.

- Promote social ties among students: Learning through the senses are unique opportunities to foster social interaction among students in the classroom. Engage students in cooperative games and challenges. Group students in multilingual teams to perform an experiment.

- Focus on the goals rather than on specific content: Keep an emphasis on what’s important for students to understand and the core of the concepts, rather than naming an overwhelming amount of species, parts, or processes.

- Don’t correct English in a science classroom: The science classroom is an opportunity to learn vocabulary of animals, body functions, and natural objects, but it’s not the context to correct someone’s English. Focus on communication rather than correction.

- Push students higher from their entry level in the language: Actively initiate conversation with the bilingual student even if they don’t respond. This pushes the student out of the entry level in the language, and helps the student feel noticed and cared for. Ask the student use visuals or realia to demonstrate learning. When you least expect it, you’ll get a complex response from the same shy bilingual reluctant to talk.

- Keep highly-structured moments in your daily science lesson: Bilingual students are constantly dealing with two or more languages in their brain, which may be overwhelming. If you overstimulate it with too much excitement may lead them to fatigue sooner than to other learners. It’s important to keep a balance between an exciting activity, and classic moments of lecture, listening, and thinking. Exciting activities may take you longer to prepare as well, so you also want to avoid overwhelming yourself/.

Involving as many parts of the brain as possible creates multiple paths for the students’ cognition to incorporate new knowledge (A Nervous Journey). Using visuals help a lot get meaning across for learners of English, but adding touch and movement add more parts of the brain to the process. In terms of Krashen’s affective filter, touch and movement reduce the anxiety. However, adding taste and smell may activate pleasure reactions that make students lose focus. Too much relaxation may not conduct to learning. It’s been said, about teaching math, that some stress is necessary to foster learning (Dewey, 1907, Hiebert & Grouws, 2007, p. 388).

Kinesthetic directions:

Modeling a skill slowly for bilinguals a form of direction by movement, where “kinesthetic” means=doing. That means, doing something slowly provides implicit directions to the student.

I found a video where an instructor explains how to build toy race cars out of recycled material. You don’t need to watch it all, and yes, this instructor speaks really fast, yet he does something quite well to face his global YouTube audience: he goes step-by-step performing the actions he instructs audience to do. You could follow the instructions just by watching what she’s doing even not understanding a single word.

When having students do crafts, a science experiment, or even when teaching a game, use a step-by-step demonstrated format.

DO and DONTS of crafts and labs:

DO

- Show your materials and state the names of the materials as you show them. Real objects as visuals are called realia.

- Break the actions needed to do the craft into sets of steps, even when they seem obvious. For some students it may not be obvious how to open a jar of painting, or how to dry off the brush.

- Name each of the action with an easy name and structure in English. For example, “Let’s cut the paper” or “Let’s glue the stones”. Keep using “let’s” again and again, again and again.

- Perform the action yourself right after you have stated the direction.

- Practice doing the craft or experiment before bringing it to the students to avoid unwanted results during performance.

- Keep explaining the craft at the slowest pace possible even when some students are moving faster anticipating steps.

- If a student asks a question about something you just said, gently repeat the same direction as many times as possible as if it were the first time ever. Even attentive students may have random lapses of divert attention when performing complex tasks.

- Keep it simple. When you plan an exciting activity, try to keep it as simple as possible.

DON’T

- Don’t assume that all students will know what to do especially if it’s a common craft, experiment or game you do at school. For example, using pipe cleaners is not a usual craft we do in Latin America, and Latino students may need a thorough explanation from scratch as something super exotic.

- Don’t overlap steps even when they are quite related. Always break the steps in as small as possible segments.

- Don’t change the sentence structure when stating the main action. For example, “Let’s cut the paper. Now we’re going to glue it. The stone must go one of top of the other”. Instead, say: “Let’s cut the paper. Let’s glue it. Let’s place one stop on top of the other”.

- Don’t rush the explanation even when you see most students going ahead of you. The one student who is falling behind is the one who needs you in front of the explanation.

- Don’t shame the student who asks you something that you just said. Brain could work in random sequences of attention while dealing with complex tasks.

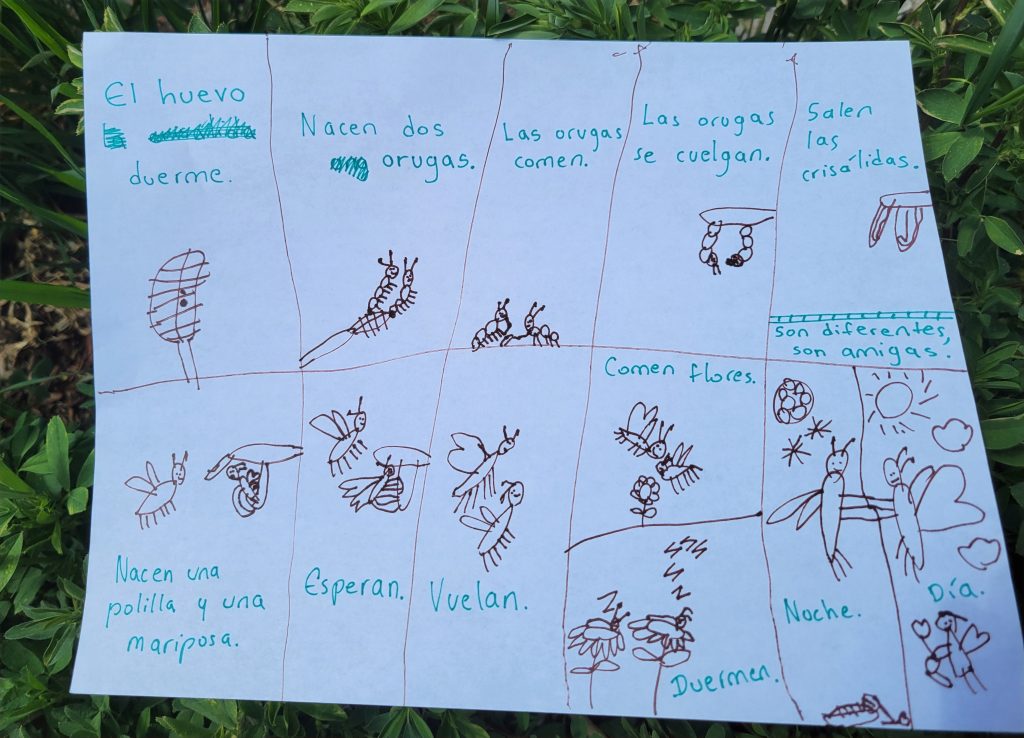

Sabina’s butterfly cycle

Students may have different valuable strengths. Not only reading and writing are important. Some are good at drawing and painting, some are good are singing and playing music, others are good at sports, among many types of intelligence they can bring to the classroom (Gardner, 1983). For this reason, letting students show what they know through various types of skills provides foundation for an equitable classroom.

My bilingual daughter depicted the butterfly cycle by comparing polillas (=moths) with mariposas (=butteflies). When they turned into adults, one goes out in the noche (=night) and the other during the día (=day). Even when they’re that different, both are similar because they hatched out of a huevo (=egg), they were orugas (=caterpillas), and they changed their shapes in a crisálida (=cocoon). One of them took longer to come out of the crisálida, but the other waited outside.

Sabina expressed the stages of butterfly’s cycle with only drawing. I used simplified Spanish to write down the stages and provide comprehensible input that she can use to gradually develop Spanish literacy. I made a couple of errors which I scratched out. Leaving error visible helps normalize translanguaging as a valid process of unsuccesful tries that often happen in communication, especially for bilingual speech.

Bilbiography

UNDER CONSTRUCTION

Bruner, J. S. (1983). Child’s talk: Learning to use language. Norton.

Dewey, J. (1907). The school and society. University of Chicago Press.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Hiebert, J., & Grouws, D. A. (2007). The effects of classroom mathematics teaching on students’ learning. In F. K. Lester (Ed.), Second handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 371–404). Information Age Publishing. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Second_Handbook_of_Research_on_Mathemati/B_onDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=The+effects+of+classroom+mathematics+teaching+on+students%27+learning&pg=PA371&printsec=frontcover

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press.

Samway, K. D., Pease-Alvarez, L., & Alvarez, L. (2020). Supporting newcomer students: Advocacy and instruction for language learners. Norton/Tesol Press.

“A Nervous Journey: What Are the Regions of the Brain and What Do They Do?” Ask a biologist. University of Arizona. Retrieved from: https://askabiologist.asu.edu/brain-regions