1 Bilingualism

The bilingual continuum

The native language of a person is considered their first language, or language number 1, so the abbreviation used is L1. The language learned after the native language is called the second language, or language number 2, so the abbreviation used is L2. In terms of acquisition, the acronym for second language acquisition is L2A or SLA. When some is trying to learn a language in a school setting, the intended language is called the target language, and the learner is called a scholarized bilingual. This happens through learning. When someone develops a language spontaneously without schooling, the process of acquisition (not learning), and this type of bilingual is called a spontaneous bilingual. See Grosjean (1982), Zentella (1998), Baker (2011).

Every bilingual has different proficiencies in each of the languages they speak, with a strong and a weak language. Oftentimes the strong language is the same language spoken by the mainstream community, or the larger region where they grew up. Sometimes the weak language is so weak the bilingual only understands it, being a passive bilingual. Other times the bilingual was active in both languages, but then gradually forgot the native language, this is called attrition (Schmid, 2011). Or the opposite, the bilingual was passive for around two years, and suddenly, started talking so fast that leaves their teachers and parents astonished. This person was just going through a passive period, just like a baby who just does babbling and cooing for around the first two years of life.

The Critical Age Period

Noam Chomsky thought the language is a pre-arranged structure in the human cognition. Acquiring a native language is about forgetting all structures we won’t use in our native language, and filling that up with the lexicon and sounds produced by our caregivers. The Universal Grammar is that set of structures we are born with (Chomsky, 1957).

If someone acquired the native language under normal circumstances, the UG remains open up to around 10 to 11 years old! That means, someone who speaks Spanish or Navajo at home and starts acquiring English by 9 or 10 years old, they will acquire English as any baby or toddler playing around with their moms. The Critical Age Period of Language Acquisition is is the time frame from birth to later in life when a language is most likely to be acquired natively (Lenneberg, 1967). It includes:

-

- L1 Critical Period: An individual deprived of language exposure until around 5 or 6 years old may struggle to attain fluency in their L1.

- L2 Critical Period: An individual who starts learning an L2 at around 10 or 11 years old may still attain a native-like command of the language.

Types of learners

- Early learners: When a person starts learning any language in childhood and keeps consistent socialization in that language, they may take a longer silent period, but once they are developmentally ready to produce the language, they will sound like a native speaker. This person does not benefit from memorization of rules, pronunciation, or vocabulary, and they don’t benefit from corrective feedback at all. They just need a group of teachers and peers who are willing to speak to them (see Samway, Pease-Alvarez, & Alvarez, 2020)

- Adult learners: When a person starts learning an L2 passed 13-14 they don’t have access to the Universal Grammar to attain a native command of the language. They are adult learners even when they look as young as 13 and 14. To learn the L2, adult learners need to be told the rule explicitly, with explicit corrective feedback, and perform conscious repetition and memorization of the rules and vocabulary. They still will learn more efficiently than someone who starts studying a language at 30 or 40 years old. At the beginning adults may move faster than early learners, but after a point they remain stagnant in certain sounds, structures, and vocab (see Patkowski, 1980, Krashen, 1982).

The optimal age for language acquisition is 7 years old (Johnson, & Newport, 1989). Before that, the child may take longer to learn because they will start learning as any baby. At 7 years old, however, the child has a mature brain to reason about grammar and pronunciation, while at the same time having cognitive plasticity to acquire the second language as a native speaker. After 9 or 10, the ability to acquire a second language natively starts to decline.

Implications for teaching:

Learners who start acquiring a second language 7 years old or younger: Teaching should focus on meaning. Examples: games, role play, social activities (with other learners and with native speakers of the target language, field trips, songs, theatre performance, art projects (Samway, Pease-Alvarez, & Alvarez, 2020).

Learners who start acquiring a second language 11 years old or older: Teaching should focus on form (Ellis, & Shintani, 2014), Krashen, 1982) . Examples: explain grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary, provide corrective feedback, and gradually scaffold meaning-based activities.

Learners at the threshold (by 8-10 years old): Teaching should blend focus on form or meaning. Short grammar explanations with fast-scaffolded meaning-based activities.

The Spanish language has a highly transparent and consistent spelling system with respect to its pronunciation. For this reason, students only need only one year to sound out all potential words in Spanish (Baique Berrocal, 2019, Cotto Pidgeon, E& Flores Reyes de Reichenbach, 2022). Spelling instruction only starts on first grade, and by the end of first grade, a student may become an independent reader.

No literacy teaching happens in preschool or kindergarten in Hispanic countries. For this reason, a Hispanic student who starts first grade in the United States may not have developed letter-naming or phonemic awareness. If the child arrived in the United States after the second grade, the student has the phonemic awareness in Spanish, and can transfer those skills to English (Dębski, & Rabiej, 2021).

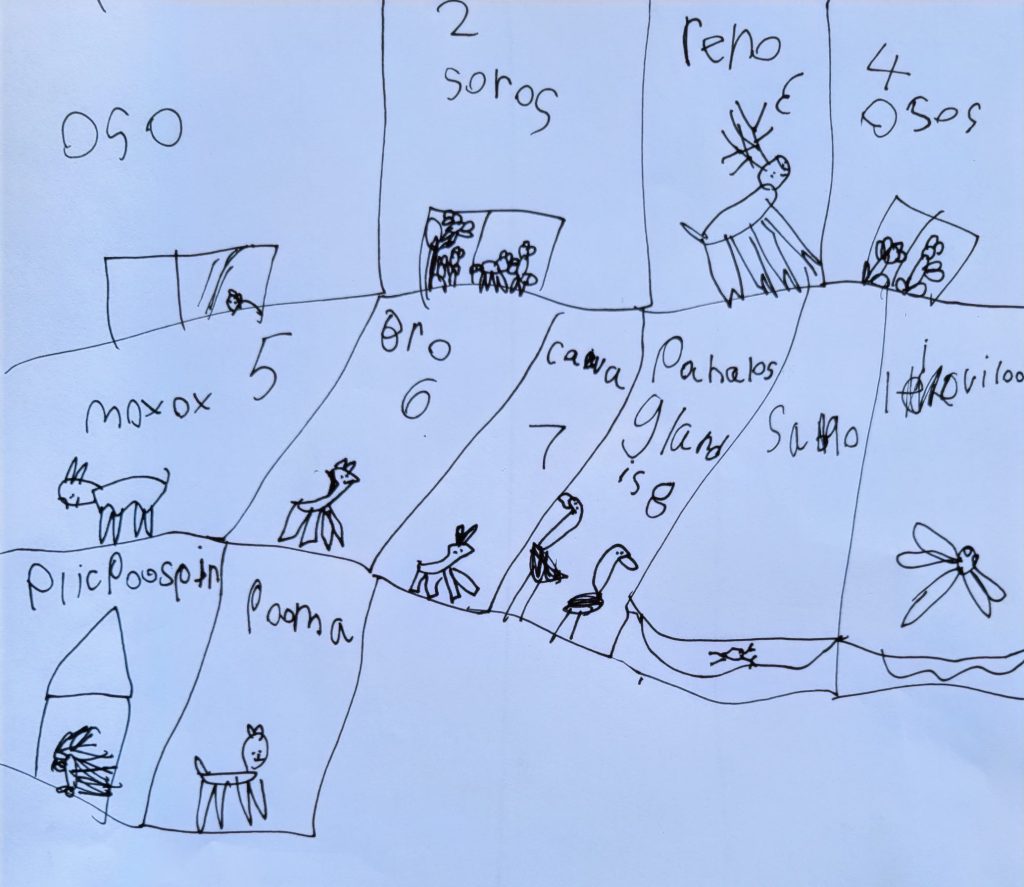

A story about my bilingual daughter. She was born in the United States, but it’s a fluent bilingual. I read books in Spanish to her. During her first grade, she spontaneously tried to write in Spanish by combining spelling patterns from English and Spanish. In the following drawing, she speaks about wild animals in Colorado after a zoo visit.

Sabina’s bilingual writing production: 1. Oso (=bear), 2. Zorros (=foxes), 3. Reno (=Elk), 4. Osos (=bears), 5. Muskox, 6) Burro (=donkey), 6) Cabra (=goat), 8. Pájaros Grandes (=big birds), 9. Sapo (=toad), 10. Libélula (=dragón fly), 11. Puercoespín (=porcupine), 12. Puma (=mountain lion)

Sabina’s writing in Spanish with English spelling

Bibliography

This bibliography guide is a work in progress. Feel free to email me at adiazcoll@gmail.com if you find any reference that requires citation.

Baique Berrocal, M. E. (2019). Conciencia fonológica y aprendizaje de la lectoescritura en estudiantes de primer grado de la institución educativa 8190. M.A. Thesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo (Peru).

Baker, C. (2011). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (5th ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Brisk, M., & Harrington, M. M. (2010). Literacy and bilingualism: A handbook for all teachers. Routledge.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. Mouton.

Cotto Pidgeon, E. I., & Flores Reyes de Reichenbach, M. G. (2022). El método fonológico comprensivo: Un aporte a la enseñanza y aprendizaje de la lectoescritura en español. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 48(2), 327-349.

Dębski, R., & Rabiej, A. (2021). Emergent Literacy in Bilingual Children. Teaching for transfer and biliteracy. Socjolingwistyka, 35, 77-87.

Grosjean, F. (1982). Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Harvard University Press.

Ellis, R, & Shintani, N. (2014). Exploring Language Pedagogy through Second Language Acquisition Research. Routledge.

Koda, K., & Zehler, A. M. (Eds.). (2008). Learning to read across languages: Cross-linguistic relationships in first-and second-language literacy development. Routledge.

Krashen, S. (1982). Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition. University of California.

Johnson, J. S., & Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21(1), 60–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(89)90003-0

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). Biological foundations of language. Wiley.

Patkowski, M. (1980). The sensitive period for language acquisition: A critical look at the critical period hypothesis. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 6(2), 147–153.

Samway, K. D., Pease-Alvarez, L., & Alvarez, L. (2020). Supporting newcomer students: Advocacy and instruction for language learners. Norton/Tesol Press.

Schmid, M. S. (2011). Language attrition: The neglect of language in bilingualism research. In J. W. Schwieter (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of bilingual processing (pp. 447–466). Cambridge University Press.

Zentella, A. C. (1998). Growing up bilingual: Puerto Rican Children in New York. Blackwell.